In July of 2017, Charlotte’s Web cannabidiol oil made a brief appearance on the shelves at Target. Charlotte’s Web— which is marketed as “a hemp extract oil dietary supplement”—was quickly removed from Target’s site, but not before stirring a murky pot of confusing beliefs on the legal regulations surrounding hemp versus cannabis. In response to an article on the subject, the Drug Enforcement Administration issued a statement to the Cannabist to correct a “misconception that some have about the effect of the Agricultural Act of 2014 (which some refer to as the ‘farm bill’) on the legal status of ‘Charlotte’s Web’/CBD oil.”

Target didn’t comment on the specifics but the event illustrated the ongoing confusion regarding the legal status of “hemp” versus the legal status of “cannabis.” What technically differentiates these plants? What products are permitted to be created and distributed under the Farm Bill? And which products are federally illegal and can only be sold in states with legalized cannabis markets?

To dig deeper into this subject, I consulted Dr. Mike Villa, PhD a plant ecologist who cultivates “hemp” under the Farm Bill and “cannabis” as a registered caregiver under state regulations in Colorado. I also spoke with Eric Steenstra, the founder of Vote Hemp and an activist and lobbyist who has worked on hemp legalization causes for over 23 years. In this study, we’ll analyze the following:

- What is the difference between “cannabis” and “hemp?” We’ll examine the colloquial usages, the scientific definitions, and the political and regulatory meanings.

- What are the issues with separating the hemp industry and the cannabis industry? Why does it make sense? We’ll untangle the complex web of political history surrounding the cannabis sativa plant and head back to the nineties when hemp activists first introduced legislation to regulate hemp under the Farm Bill.[1]

- What is the future regulatory structure for hemp and cannabis companies? We’ll look at the latest version of the Industrial Hemp Farming Act and examine shifts in the regulatory definitions of “psychoactive cannabis” and “non-psychoactive cannabis” across the world.

When I set out to write this article, I wanted to know if the barriers between the industries were dissolving. Will changes in international legalization change our traditional definitions of hemp vs. cannabis? What will these industries look like 10 years from now? My research evoked politics, semantics, and science and the answers were surprising.

What is the difference between “cannabis” and “hemp?

Given that our language affects the way we think, let’s start with the familiar definitions. You’ve probably used the word cannabis (or its slang: marijuana) to describe a Cannabis Sativa plant that is bred for its potent, resinous glands (known as trichomes) found in the buds of the plant. These trichomes contain high amounts of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the cannabinoid most known for its psychoactive properties. Colloquially, “hemp,” refers to non-psychoactive cannabis, bred for the production of seed and fiber. In fact, during the medieval era in Europe, “haenep” (the word hemp’s Old English predecessor) was a generic term used to describe fiber from any plant.[2] Hemp seeds are a good supplement for nutritious smoothies, and its fibrous stalks can be utilized to make textiles, cloth, rope, and biofuel.

These colloquialisms are so embedded in the American lexicon, it’s hard to believe that hemp and cannabis products come from the same plant. However, according to Dr. Villa, there is no technical difference between the taxonomy of “cannabis” and “hemp.” Both hemp varieties and marijuana varieties are of the same genus, Cannabis, and the same species, Cannabis Sativa.[3]

“There are four distinct lineages of cannabis: cannabis sativa, cannabis indica, cannabis ruderalis, and cannabis linnaeus. From a regulatory standpoint, we are using the 0.3% THC level [to define hemp], but that 0.3% can be grown in a Cannabis Sativa or can be grown in all four lineages.”

Villa is referring to the accepted regulatory definition of hemp: “non-psychoactive cannabis sativa containing less than 0.3% THC.” This definition was first introduced in 1976 by Canadian plant researcher, Ernest Small. In his publication, A Practical and Natural Taxonomy for Cannabis, Small declared that there was no scientific way to distinguish between cannabis and hemp, so he proposed separating them based on arbitrary THC levels. [4]

More than forty years later, Small’s definition has stuck around. Across the world, the regulatory distinction between cannabis and hemp is not related to the plant’s genetics or origin, but how it is bred.

“As with all other crops, we have selected for or against certain traits,” said Dr. Villa, elaborating on his work as a plant ecologist. “We have been successful with breeding out THC, and crossbreeding and back breeding and stabilizing, and it wouldn’t matter whether we call it one versus the other. They can all be bred. The fact that we have a regulatory definition has allowed us to work with all four lineages to produce medicinal plants.”

So scientifically they’re the same. But in the political sphere, hemp and cannabis are completely different beasts. Why?

In the early nineties, Eric Steenstra was an entrepreneur and the co-founder of Ecolution—a company importing hemp textiles from Eastern Europe. His business was facing challenges sourcing materials in Post-Communist countries, and he saw an opportunity to cultivate hemp in the US. Steenstra began lobbying for hemp legalization in the United States, and Vote Hemp was born shortly thereafter.

“It made a lot of sense to have American farmers and source it closer to the market. We knew that it had been grown here for centuries—long before the founding fathers—and all the way up until the 1930s. We knew it would grow here, and we knew it made economic sense.”

At the time, there were only 150 members of the hemp trade association and the country was still swirling in “Just Say No” drug propaganda. Creating a strong distinction between “hemp” and “marijuana” was crucial in efforts pushing legalization efforts forward. Steenstra acknowledges that this was partially due to the minds of politicians.

“When we talked to lawmakers, friendly or not friendly, they didn’t want to look at cannabis laws. They wanted to consider different aspects of it,” said Steenstra. “The argument of why a farmer could grow hemp was different in their mind from whether someone could or couldn’t smoke marijuana. We felt that we had to go to them to talk about that.”

Steenstra and his team spent over a decade educating lawmakers and farmers on hemp, before passing their first bill in 2005. Their principal cause: to change the laws to allow American farmers to grow hemp. Steenstra and his fellow activists emphasized the economic opportunities and went from office to office of politicians, explaining that the shape, appearance, and usage of hemp was different.

“Congress people began to think of rope vs. marijuana,” said Steenstra.

The legalization movement was successful across party lines. Farmers began cultivating it across the country and the total hemp acreage increased year-after-year.

Cannabidiol oil? The connecting point?

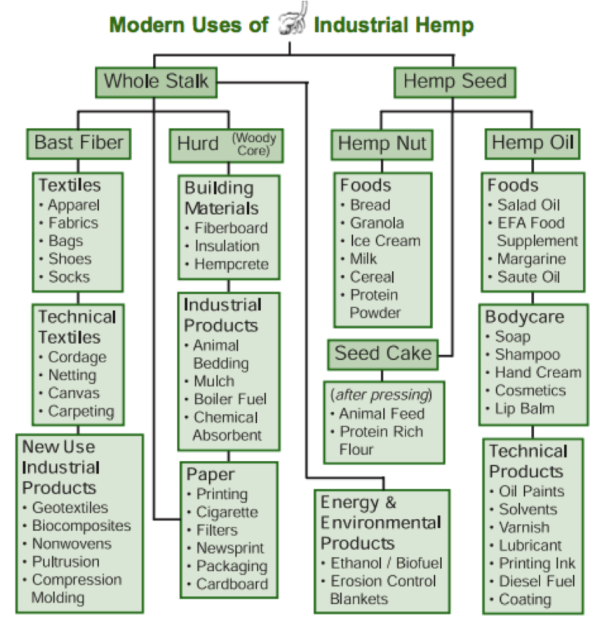

A few years ago, the semantics classifying “hemp” vs. “cannabis” grew murkier. Vote Hemp had focused on promoting legislation for “industrial hemp,” emphasizing that the stalks of the hemp plant could be used for clothing, canvas, and rope, the woody core fiber of hemp stalks could be used for biofuel, and the seeds could be used for food and body care products.[5]

Graphic from Vote Hemp’s Report: “Why Hemp?”

In 2013, CNN premiered the documentary Weed, which was serious nationwide publicity for the therapeutic medicinal cannabinoids in non-psychoactive cannabis. Hemp could no longer just be considered rope. Its flowers contained medicinal cannabinoids and hundreds of patients and their families moved to Colorado to seek it out.

Although this wasn’t a new revelation, it began dissolving the barrier distinguishing “hemp” and “cannabis.” The Farm Bill of 2014 [6] had defined “industrial hemp” as with less than 0.3% THC.[7] The regulations had not specified that “industrial hemp” could only come from the stalks and the fiber. This seemed to leave a gray area open to interpretation—could cannabidiol oil from the flowers of the plant be sold and regulated under the Farm Bill in states with the requisite agricultural regulations?

Well, this is where it gets tricky and the DEA’s position isn’t clearing anything up. Their response to the legal status of Charlotte’s Web, which could be a precedent for any Cannabidiol oil sold on the mainstream market:

“It is generally believed that the material is an extract of a variety of the marijuana plant that has a very high ratio of cannabidiol (CBD) to tetrahydrocannabinols (THC). Because this extract is a derivative of marijuana, it falls within the definition of marijuana under federal law. Accordingly, it is a Schedule I controlled substance under the CSA.”

So as it stands currently, Target can sell hemp seeds in its grocery aisle, but can’t sell the processed cannabidiol oil in its nutritional supplement section. They both contain less than 0.3% THC, but because one can be traced to its slang “marijuana,” it is forbidden under the Controlled Substance Act.

Why should we keep hemp and cannabis separate?

Villa and his team cultivate acres of hemp under the Farm Bill, but only a few thousand square feet under Colorado caregiver regulations. Their “hemp” plants and “cannabis” plants are kept on separate properties. Despite this separation, 90% of their harvested hemp and cannabis crops are utilized for medicinal purposes and distributed directly through a physician referral network.

“Technically, the only difference is we’re not working with THC at all,” Dr. Villa said of his hemp property.

I asked Dr. Villa if he thinks this separation makes sense. Will we ever be able to have a more nuanced understanding of the cannabis plant? Will our legal definitions ever reflect the growing body of research that illustrate that this plant that can have psychoactive effects or non-psychoactive effects depending on how it is bred?

“I don’t necessarily think they should be separated. But I don’t want to see industrial hemp regulated in the same way as medical marijuana,” said Villa. “I know there are people interested in merging those two things together. I don’t know if it will ever happen because of the stigma with medical marijuana.”

Villa believes the bigger issue facing the hemp industry is the arbitrary limitations for THC. He faces obstacles breeding and experimenting with new hemp strains, when their THC levels cannot surpass 0.3%

“It really sucks, because we could have a much more effective product without compromising the CBD,” he said. “We know from experience that we can take the high out and mask the psychoactive effectives. The THC in its own right is really good for anti-inflammatory purpose.”

On the other hand, keeping the industries separate, and maintaining distinctive regulatory definitions has been key for the hemp legalization movement. Vote Hemp has calculated that the amount of hemp cultivated across the country increased from 9,600 acres in 2016 to 20,000 acres in 2017.[8] New legislation regarding hemp regulations was introduced before the congressional recess in August and could be expected to become law by 2018.

“Passing this legislation will fully remove it {hemp} from the Controlled Substances Act. It will continue to open up the market,” said Steenstra. “It will also aid significantly with research. We’re missing infrastructure and genetics—the USDA used to have a researcher that grew and bred hemp varieties and did research on it and came up with the best hemp varieties. Those have all been lost. All that’s left is wild feral hemp. We’re really starting over.”

If I learned one thing from my research, the semantics are around the subject are precarious. The barrier between these two industries is dissolving, as Charlotte’s Web’s brief appearance at Target demonstrated, but the line remains drawn in the sand.

Removing industrial hemp from the Controlled Substance Act would be a major win for hemp farmers across the country and could have massive implications for a number of industries (like biofuel, textile, and food) to reduce dependence on non-renewable resources. So before that happen, perhaps it’s best to not rock the boat too much.

Conclusions

When I first started writing this article, I was reading through the legal regulations in Colombia, which legalized medical cannabis in November of 2016. The regulations outlined distinctive regulations for two types of cannabis: “psychoactive cannabis” versus “non-psychoactive cannabis,” implying that non-psychoactive cannabis could be used for medicinal or industrial purposes.

How logical, I thought. I wondered if this could be the future. Perhaps we could shift our understanding of hemp versus cannabis to psychoactive cannabis vs. non-psychoactive cannabis?

“Do you think international regulatory definitions could change our semantics around the subject?” I asked Steenstra.

“Hemp has been used in all of the folk stories,” Steenstra said. “I don’t think the word is going anywhere.”

But where the United States might get some inspiration from the international movement is a shift in the arbitrary levels for THC restrictions. Regulations in Colombia and Mexico are defining non-psychoactive cannabis as cannabis with less than 1% THC, which is a departure from the antiquated 0.3% THC levels. The newest version of the Industrial Hemp Farming Act would permit researchers to be able to work with hemp with up to 0.6% THC levels.

“I hope we get to a place where we realize that there isn’t something magical that happens when we get to 0.4% THC,” said Steenstra, “The arbitrary standard is a bit low.”

Sources & Footnotes:

[1] The Agricultural Act of 2014 (H.R. 2642; Pub.L. 113–79, also known as the 2014 U.S. Farm Bill), formerly the “Federal Agriculture Reform and Risk Management Act of 2013”, is an act of Congress that authorizes nutrition and agriculture programs in the United States for the years of 2014-2018.

[2] David, P West, PhD. “Hemp and Marijuana: Myths & Realities.” 1998. North American Industrial Hemp Association.

[3] Small, Ernest and Arthur Cronquist. “A Practical and Natural Taxonomy for Cannabis.” International Association of Plant Taxonomy. Vol. 25, No. 4 (Aug., 1976), pp. 405-435.

[4] C. sativa is tall and laxly branched with relatively narrow leaflets, C. indica is shorter, conical in shape, and has relatively wide leaflets, and C. ruderalis is short, branchless, and grows wild in central Asia.

[5] The “Vote Hemp” Report © 2002 Vote Hemp, Inc.

[7} From Section 7606: INDUSTRIAL HEMP.—The term ‘‘industrial hemp’’ means the plant Cannabis sativa L. and any part of such plant, whether growing or not, with a delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol concentration of not more than 0.3 percent on a dry weight basis.”

[8] This acreage estimates includes hemp grown for industrial purpose and medicinal purposes. (It would include Dr. Villa’s farm and Charlotte’s Web’s operations.)

Recent Comments